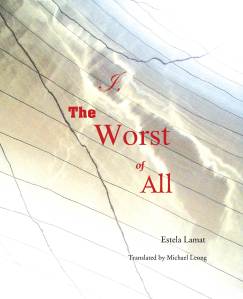

Learning to read Estela Lamat

I’m about to receive a large stack of English 101 papers tomorrow and to get my grading muscles primed and ready, I’m going to offer a free on-line tutorial.

But instead of papers about fiction writer Tim O’Brien and cultural critic Virginia Postrel (this is part of the required curriculum at Rutgers University), I’m going to focus tonight on Isabel O’Toole’s “Narcissism and Doubt”—a largely negative and terribly misguided review of I, the Worst of All that recently appeared in The Latin American Review of Books.

Quotations from Ms. O’Toole’s piece will be followed by my comments in brackets.

THE CHILEAN Estela Lamat endeavours to explore a realm of poetry that is usually forgotten and her use of free verse and poetic prose is ambitious and complex, yet it is hard to see past her arrogant, self-assured style and uncover the true meanings within this doubt-ridden work.

[You should more rigorously define what you mean by “true meanings” here. In fact, are there “true meanings” in Robert Browning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” or in Alfred Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” (From your writing, I’m assuming that you would feel more comfortable with 19th C. British poetry) or Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market”? Had you been present in our discussions of O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story,” you probably would have been less tempted to essentialize “truth” or, to quote Keats, to read the text with an “irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Even the wildly popular and much maligned Billy Collins knows this when he writes in his “Introduction to Poetry”:

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

I’m sure he would say, “Just put the hose down, Ms. O’Toole.”]

Although the wide gaps between some two-line poems may be interpreted as a meaningful silence, they may also be classed as a waste of paper. Not enough is communicated to the reader within these short poems to justify the huge silence between them. Although the lack of order may have been intentional, off-hand it seems amateurish and as if not much thought has gone into its organisation.

[I take it you’re talking about a two-line poem such as this one from the first section:

And since we’re in cyber-space here and not concerned about wasting paper for the sake of poetry, we might also consider this one-line poem which has an epigraph that nicely refutes Neruda:

There is a type of poem called the epigram (you might want to read some Martial or some of the Hellenistic poets but perhaps you might think those Greeks were wasting precious stone with their silly inscriptions) and Lamat is surely playing with the compression and constraint of the satiric epigram as opposed to the utterly expansive prose poems that follow in the second section. I think, in fact, you are the one who missed the book’s dialectical structure.]

Much of this collection centralises on the necessity of understanding “the poem”. Though in no way a doctrine, Lamat gets so wrapped up in trying to decipher what it is that defines a poem that she ends up becoming self-indulgent instead of self-reflective [sic].

[This is a gross misinterpretation of Lamat’s poetics. If we examine a poem like “How a poem ends” (which is less a classical ars poetica and more akin to Julio Cortázar’s “How to” pieces), we immediately realize that Lamat is not offering a positive definition of what a “poem” should be (and putting quotes around the word “poem” is already missing the point)—in other words, for Lamat, the ideality of the poem is not the real issue but rather the materiality of the text, the black marks that we sensually experience against the white page.]

[Final Remarks: I suggest doing a lot of reading. You might want to begin with William Carlos Williams’ “The Poem as a Field of Action” and go on to study George Oppen and the way he “wastes paper” by creating gaps in his poetry. You might also want to read Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation” and write the sentence “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” on the front cover of your copy book. And it would probably help you to catch up on some post-Newtonian science… I wish you better luck on future reviews. Paper Grade: C / C+]

*

…a poem ends when it’s obvious

when the poem’s fingers caress your nape at the poem’s end

it is just then

when a poem begins

then its conclusion is a beginning

then a poem is a door

but it’s also a knife

and it’s also a red wound filled with kisses

a poem ends exactly there

where something not made of letters begins

a poem ends when the poem concedes its own death

that it died before ever becoming a poem

that it died when it was there

spinning free

that it died when it was born into the life of the poem.

A poem is always a death

and only thus does a poem end.

—Estela Lamat, from “How a poem ends”

It’s always disappointing to receive a review that seems not to have done what readers should do–which is, to struggle beyond their own pre-set version of taste to reach what the work itself offers. Take heart, Michael. Even a negative review is important, because it means that people are reading the work, and think it worthy to critique. In an age of so many books, no publicity is bad publicity.

Thanks for the encouragement, Phil. I really appreciate it. I suppose you’re right, that even a negative review creates some kind of discussion.

I was just so ticked off by the review’s nasty dismissiveness and what I felt to be a non-reading of the book that I had to respond with this parody.

May we all struggle beyond our own pre-set versions of taste. I’ll drink to that!

Oh, Michael. This is by far the most pedantic and arrogant review I have ever read! It took me a tremendous effort to get past her arrogance. I found this review to be fundamentally conservative and racist! I am Latin American and I find it extremely offensive when people assume I should speak about my identity. Is O’Toole forced to write as a European? What is that colonial attitude toward Latin American writers? You should have suggested some post-colonial literature for her to read. She should start by understanding the concept of exoticism. Blasphemous! I read your translation of Lamat and her book IS NOT about the poem, so there should be a little bit more sharpness when falsely critizicing a book.

O’Toole talks about Lamat’s beautiful images but she never even provides an example of these images, even less an analysis of them. I found her review to be very juvenile and arrogant; she tries too hard to be “intellectual.” I believe it is a very poor review and a very monotonous (and failed) attempt to built herself as a “critic.”